History Lesson

Published 6:17 pm Friday, February 25, 2022

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By CHERYL DELOATCH

Correspondent

First of a two-part series

WINTON – Did you know that Winton was the first town in the South that was burned during the Civil War?

This and other interesting facts were shared at a lecture given this month at the Albemarle Regional Library in Winton.

Libby Jones, President of the Winton Historical Association, Inc., introduced the speaker and gave the lecture’s purpose.

“Today’s lecture recognizes the 160th anniversary of the Burning of Winton,” said Jones, noting that the Winton Historical Association co-sponsored the event along with the North Carolina Civil War & Reconstruction History Center (NCCWRHC).

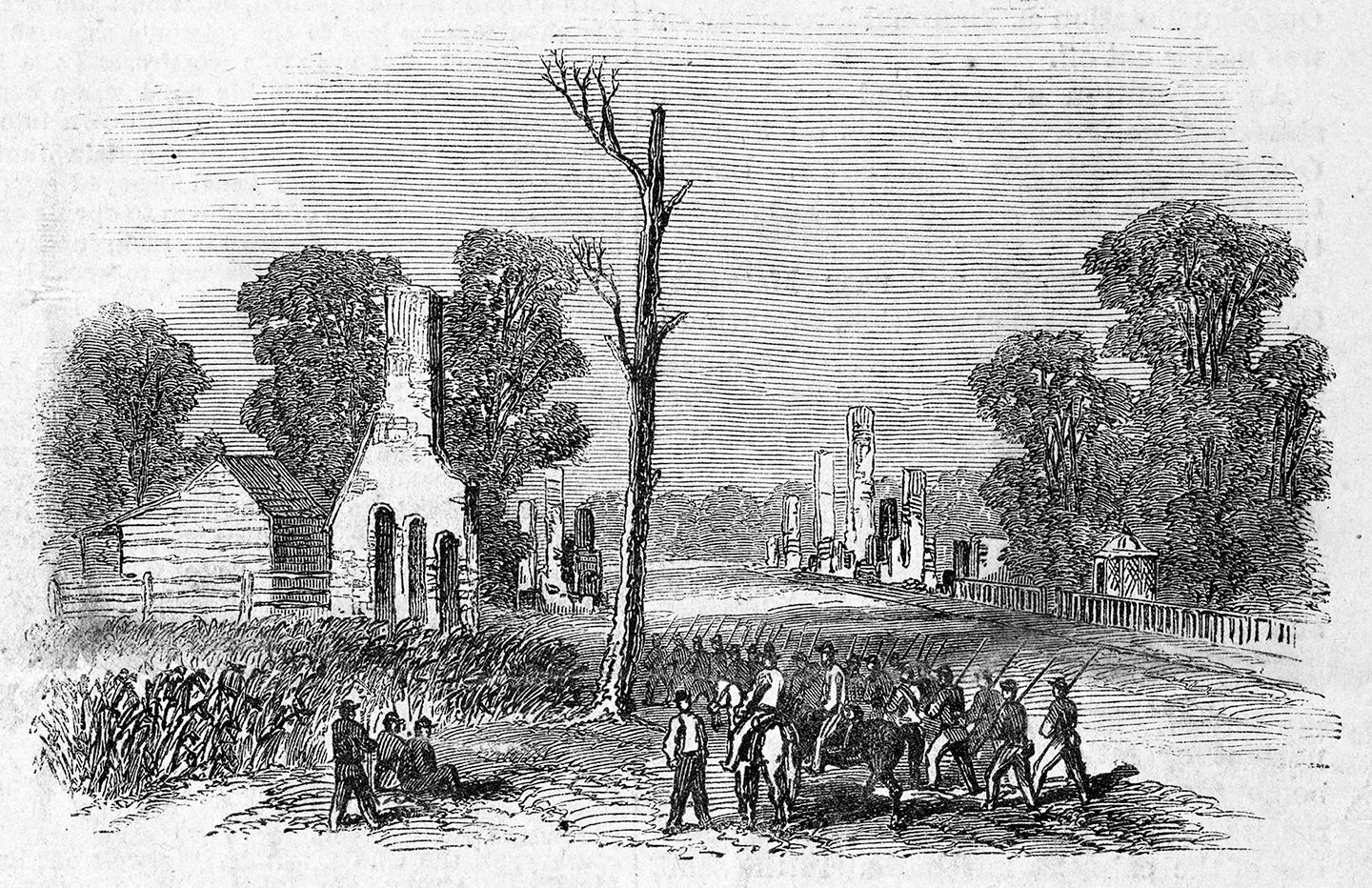

This sketch by artist F.C.H. Bonwill shows the town of Winton in ruins after Union forces burned it on Feb. 20, 1862. Contributed Photo

The featured speaker was Cheri Todd Molter, a Content Development Specialist at NCCWRHC located in Fayetteville.

Todd Molter discussed Hertford County’s role in the Civil War, using accounts from Black and white residents who were living during that time.

“The stories are diverse,” Todd Molter said.

Among the accounts was that of a mixed-race woman living in Winton, Martha Keen, who played a major role in the burning of the town.

“Cheri Todd Molter learned about Keen from one of my lectures,” said Hertford County native and historian Marvin Tupper Jones in a communication after the lecture.

Todd Molter shared this account during her lecture, saying that Keen was born in 1826 or 1827 and died in 1917. Though reported to be enslaved, Keen was free and listed in the 1860 census. In 1862, she was married to John Keen and had three children.

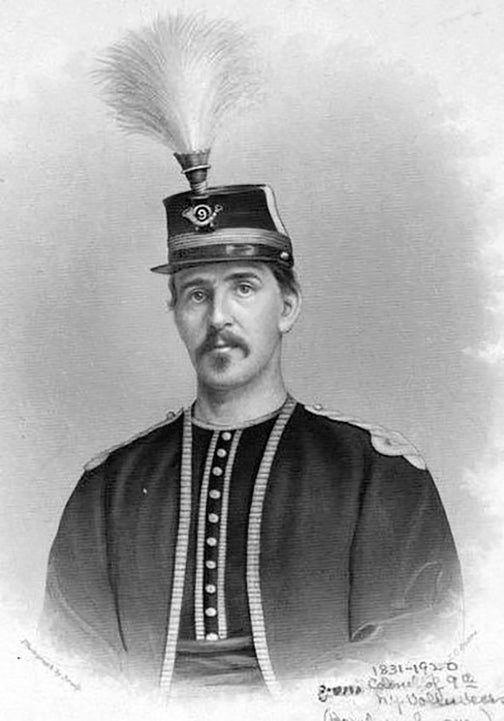

“On February 19, 1862, rebels who hoped to ambush a United States Navy gunboat forced Martha Keen to stand on the wharf in Winton to encourage the gunboat to dock,” said Todd Molter, sharing information she learned from Jones. “Fortunately, the USS Delaware’s commander, Colonel Rush Hawkins, saw the muzzles of the arms aimed at his ship and turned away as the rebels began firing.

“Were it not for the USS Delaware’s retreat, Martha Keen would have been caught between two sets of rifle and cannon fire,” Todd Molter continued. “While the rebels claimed that they paid Martha Keen and her husband John to act as a lure, it is hard to believe that a 35-year-old, married mother of three would endanger herself for pay. It is likely that she was coerced and her husband silenced.”

In his 1962 article – “The Burning of Winton” – the now late Dr. Thomas C. Parramore wrote that Roanoke Island fell to Federal forces under command of General Ambrose E. Burnside on February 7, 1862. Those forces then defeated the Confederate naval forces at Elizabeth City and occupied Edenton.

Confederate units sent to defend Winton were the “First Battalion of NC Volunteers from a camp near Suffolk, Virginia, and Company A of the Virginia Mounted Artillery from the Portsmouth area.” If Winton was taken, the Union could move on Norfolk, Virginia, and the railroad junction in Weldon, NC.

Colonel Rush Hawkins, commander of the USS Delaware, gave the order for Union troops to burn Winton. Contributed Photo

The 400 NC Volunteers were led by Lt. Col. William T. Williams of Nash County and “Capt. J.N. Nichols’ Southampton Artillery brought four pieces of artillery – no match for a gunboat. Local militia companies raised the total number of troops to above 700.

There were a total of nine Union gunboats. After Confederate muskets were fired at the USS Delaware, that vessel along with another gunboat returned fire, their guns trained on the bluffs (now the area of King Street).

The next day (Feb. 20), the Union vessels returned, causing the Rebel troops and Winton residents to flee the town.

“The last civilians scarcely cleared the town when at 10:20 a.m. several of the Federal vessels began bombarding the woods between Barfields (now called Tuscarora Beach) and Winton. Only a few shells were expended before it became clear the assault would not be contested,” Parramore wrote.

Once the Union troops came ashore, they set most of the town on fire, to include the county courthouse.

“The town was ransacked, and the personal property of its citizens was plundered. Feather beds were dragged outside, split open, and searched for hidden treasures. Furniture was smashed, and livestock was slaughtered and carried off,” wrote Parramore.

Todd Molter shared that the Union Navy kept coming to Winton and controlled the Chowan River throughout the war.

Libby Jones stated, “The troops that served Winton were dishonored but later served in other battles (of the Civil War), including the Battle of Antietam.”

Audience members participated in a question and answer session following the lecture. Todd Molter also spoke with attendants individually.

NCCWRHC’s goal is to gather and record accounts/oral histories from across the state through the “100 Stories from 100 Counties” Initiative.

A flyer explains the initiative’s goal. “Our state’s story needs room to breathe because it extends beyond those four years of war and … cannot be neatly wrapped in Confederate gray. North Carolina’s enduring legacy is more like a quilt: A patchwork of blue and gray, white and black, and various shades in between.”

NCCWWRHC’s website states that its main goal is “to create a comprehensive portrait of North Carolina history that spans the Antebellum, Civil War, and Reconstruction periods.” It adds information to histories told previously and uses new records found afterward, “patterns of data that have been newly seen, and recent scholarship. All of these things will make a valuable contribution to a new and more accurate depiction of this history that was unavailable a century ago.”

During her lecture, Todd Molter said she has only received seven stories from Hertford County so far and 517 total for the state.

“I need stories from all 100 North Carolina counties,” she said.

In a later telephone conversation, Todd Molter said a number of stories have been received from those living in the Roanoke-Chowan News-Herald coverage area. Those numbers include one story from Bertie County, four from Northampton County, and zero from Gates County.

“Oral histories need to be accurate, and transcriptions must be of academic quality,” Todd Molter said.

Stories can be emailed to her at cheri@nccivilwarcenter.org.

(Part two, which will publish next week, will focus on how the town of Murfreesboro was spared from being burned during the Civil War.)