Lessons in ‘blue’

Published 5:06 pm Tuesday, January 11, 2022

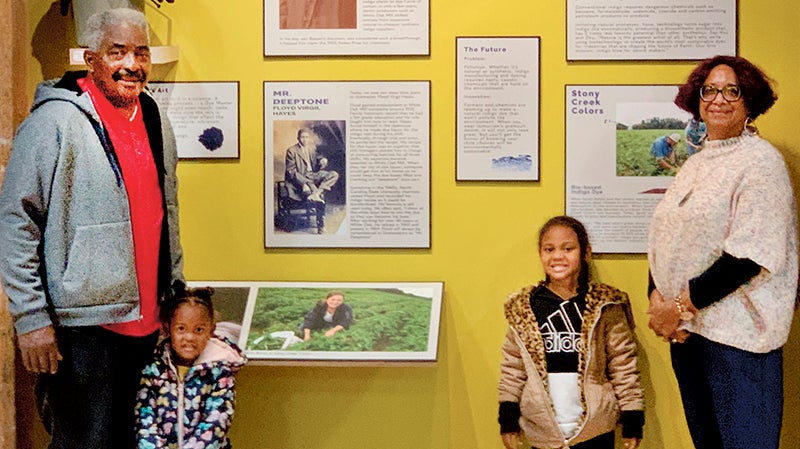

- Reba Green-Holley is shown with her husband, Guy, and their two grandchildren at a museum display in Greensboro that honors the legacy of her late grandfather, Floyd Virgil Hayes. Contributed Photo

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

GREENSBORO – Trillions of individuals around the world wear blue jeans. Some fancy the designer types, complete with rips and tears, while others wear them for pure comfort and durability.

But while they are available in different colors, have you ever wondered why a standard pair of dungarees are always the same exact shade of blue?

You can thank the grandfather of a Gates County woman for that consistency.

Reba Green-Holley, retired as Gates County’s Cooperative Extension Director, was born and raised in Greensboro. It was there that her grandfather, Floyd Virgil Hayes, perfected the recipe for the indigo dye still in use today in making denim jeans.

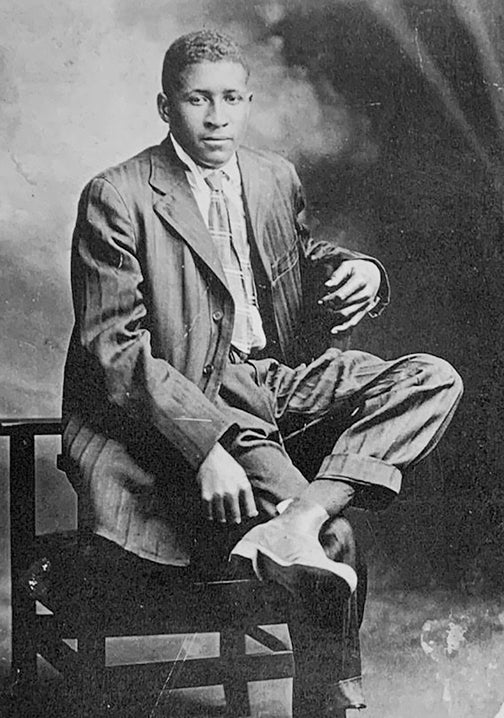

Despite having only a fifth grade education, Floyd Virgil Hayes perfected the recipe for the indigo dye still in use today in making denim jeans. Contributed Photo

While the mill he worked at closed four years ago, Hayes was once part of a team of men that earned a living in the textile industry. It was at the White Oak Mill – part of Cone Mills – where Hayes concocted the now famous indigo dye.

In late November, the White Oak Legacy Foundation (WOLF) celebrated Hayes and others who made such an impact on what was then a booming business. The event included a panel discussion on indigo dye technology, innovations in dyeing, and Greensboro’s place in the story of the blue jean. The discussion was followed by a reception for the family of Floyd Virgil Hayes.

His story has been passed down through several generations of the Hayes family, to include Green-Holley. She remembers her grandfather from her childhood growing up in Greensboro. On behalf of her family, Green-Holley thanked WOLF for all they have done to preserve and honor his legacy as an expert Dyemaster. She had the opportunity to introduce several of Hayes’ grandchildren and great grandchildren that attended the November event.

“Ever since I was a child I remember hearing the stories of my grandfather working at Cone Mills and the contributions that he made,” Green-Holley said at the Nov. 27 event. “He was a man of many talents, titles, and achievements.”

Along with his job at Cone Mills, which began in 1925, Hayes was a sharecropper, working on a tobacco farm.

“He raised tobacco to help send his four daughters to college,” Green-Holley recalled. “He would get up at 5 a.m. and work on the farm; then would leave home at 6 a.m. and drive to the mill and would be there when the whistle blew to go to work.”

His shift was from 7 a.m. until 3 p.m. Green-Holley said he would drive home, work on the farm until dark, would be in bed at 8:30 p.m. and up before daybreak the next day to do it all over again.

“Even with his Rheumatoid Arthritis, I never, ever heard him complain,” she recalled.

With only a fifth grade education and the fact that his wife taught him to read, Hayes had a knack for mastering the art of making dye liquor.

“He did it by feel and sight…he didn’t have a recipe,” Green-Holley said. “He would come home with a blue nose, ears, and fingernails; you name it, it was blue, but it was consistent every time.”

His mixture was so superior that the mill managers put him in charge of concocting the batches for all shifts. His expertise became so essential to the mill that when they ran out of dye liquor after he had completed his shift, someone would go get him at his home so he could keep the dye boxes filled and the looms kept cranking out that “deeptone” blue yarn.

“He couldn’t tell them what we did…the formula was in his head,” Green-Holley said. “In the 1940’s, the mill bosses had chemists from NC State University to come and shadow him and take samples of his dye. From that they were able to write a formula.”

Despite creating the indigo dye still famous today, Green-Holley said her grandfather retired in 1965 without being recognized for that industry standard.

“He never complained about that, he was always proud of what he did,” she said.

Even in a segregated South, Hayes was a landowner and a homeowner.

“He was a professional young man, even owning a car – a Dodge,” Green-Holley recalled. “He was well-dressed, that was something that caught the eye of my grandmother when they began seeing each other.”

Even though he mastered the formula still used in dyeing the famous blue jeans, Hayes could only earn the title of a dye maker, not a dye master.

“That was due to the society issues of that period of time,” Holley stressed. “When people would complain about their long, hard hours of work and how tired they were, he would say he didn’t have time to be tired.”

Holley closed by saying that her grandfather’s legacy of hard work and determination lives on today with family members earning college degrees in a wide variety of fields and are extremely successful in their workplaces.

“We are so thankful that the Floyd Virgil Hayes story was passed down to us and is now documented as part of Cone Mills history. Whenever you wear jeans or denim, Floyd Virgil Hayes made it blue,” she said.

The museum’s display denotes how textiles helped build the denim industry in Greensboro. It was there in December of 1921 that a patent was issued, covering a continuous yarn dye system for indigo, which today is used around the world in the commercial production of denim fabrics.

Together with the help of museum consultant Dan Spock, the expo – “Innovations in Blue” – will run until March 31, 2002.