Truth, Lies and Power

Published 11:00 am Monday, September 10, 2018

(Editor’s Note: Today, the Roanoke-Chowan News-Herald begins a three-part series about a farmer in the Boykins, VA area with ties to Northampton County who is currently locked in a legal battle with agricultural officials at the federal level. The series is published with the permission of Farm Journal.)

By CHRIS BENNETT

Farm Journal

“If I heard this story about someone else’s farm I wouldn’t believe it, but I have to because it’s happening to me. I never hid a thing, always got permission beforehand, and did things the right way,” says Charles Hood. “None of that mattered to the government.”

In the slippery realm of wetlands and NRCS (National Resources Conservation Service) swampbuster regulations, does the government win even if it loses?

In 2005, Hood purchased 30 acres of former timberland in southeast Virginia, sought USDA’s approval to improve the acreage, and met with agency officials on scores of occasions across a decade of land improvements. In 2016, NRCS came knocking and claimed he was in violation of USDA’s wetlands and swampbuster regulations.

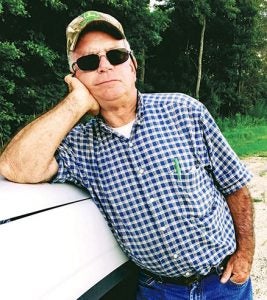

Two years later, on June 14, 2018, Hood, 62, prevailed in court when the presiding judge weighed the facts

Despite having a judge rule in his favor, Charles Hood, a Boykins, VA farmer, remains locked in a legal tussle with federal officials after he transformed 30 acres of a former tree farm into farmable land. | Photo by Brenda Young

and dismissed NRCS’ claims. Yet, Hood’s victory may ring hollow. Within weeks of the ruling, NRCS sent Hood a letter announcing a new wetlands swampbuster determination. (The letter also requested a response regarding an NRCS site visit by Aug. 10.)

Essentially, the court decision may be a mere inconvenience to a federal agency determined to place full regulatory power across Hood’s ground. Out with an old wetlands determination, in with a new one. Meanwhile, a farmer’s future hangs in the balance.

“I trusted and was lied to over and over by NRCS officials,” Hood stated. “I don’t think the judge believed a word they said. They may know how to check boxes on a piece of paper, but they don’t know a thing about farming. I’m a private man, but I want the public to know what has happened.”

The gravity of Hood’s case leads directly to uncomfortable questions for U.S. landowners: When a wetlands determination is ruled invalid in court, yet the associated agency simply pushes the reset button, does the court decision mean anything of significance to a landowner? Backed by unlimited resources, how many bites at the same wetlands apple does a government agency get?

“Not Even Close”

In 2006, just two miles above the North Carolina line, 30 acres of cutover tree farm ground came open in Southampton County, and the possibilities grabbed Hood’s attention. The 40-year, part-time employee of the Farm Service Agency (FSA) and small farmer already grew 100 acres of corn, cotton, peanuts and soybeans on 100 rented acres of adjacent farmland, and at $800 per acre, the former timber ground was priced to move. Hood was a dawn-to-dusk grinder, and he wasn’t going to allow opportunity to skate, regardless of how much restoration work might be involved.

The property was relatively flat and surrounded by ditches on all sides. Hood brought in retired NRCS soil scientist Jerry Quesenberry (1975-2005) to take a long look at potential wetlands issues.

“Jerry is as smart a wetlands expert as you’ll find and that’s what he’s done across his whole career,” Hood said. “He checked the acreage thoroughly and said it was very well drained and could make for good grain land. With the right work and cleanup, I knew I could get it ready for soybeans.”

Quesenberry advised Hood to follow procedure and check with appropriate agencies, including the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

“Charles wanted to do ditch work and I told him to check with Corps. The Corps gave him full permission to do maintenance on the existing ditches. The property is totally isolated and has very good drainage,” noted Quesenberry.

With three decades of wetlands delineation under his belt, Quesenberry is adamant: “The acreage is not a wetland and doesn’t reach the three criteria of hydrology, hydric soils and predominance of wetland vegetation. Boiled down, the property does not meet hydrology or vegetation criteria. It’s got spots of hydric soils, but even those were there prior to the property ever being ditched. It’s not even close.

“A judge has seen the evidence and hammered NRCS’ behavior,” Quesenberry adds. “But now NRCS gets to go right back to the drawing board and do it again? As a 30-year NRCS employee, I want this whole story to come out to show people how a small farmer with a tiny piece of land is being harassed by ego-driven government officials.”

Bureaucratic Crosshairs

Excited to restore the acreage, Hood leaped into EQIP (the Environmental Quality Incentives Program offered by the NRCS), pollinator plots, cover crops, minimum till, stump shearing, timber path grating, and more. From Hood’s perspective, he was improving the ground with every move countenanced by NRCS.

(NRCS declined comment on all FJ questions related to the Hood case.)

“They told me part of my land was a farmable wetland and I did all my work in the open,” Hood said. “I never dreamed I was doing anything wrong. NRCS was always involved on my land and one of their officials, Yamika Bennett, personally met with me at least 60 times over the years. She never said nothing about me doing things wrong. I trusted them all.”

(Bennett, a district conservationist with Virginia NRCS, declined comment related to the Hood case.)

By 2014, Hood had soybeans on part of the property and averaged 40 bu. per acre—close to the county average. He followed in 2015 with 35 bu. per acre. (Hood hasn’t been able to plant crops on the land since 2015.) The property was beginning to respond to restoration efforts and Hood felt he was sliding building blocks into place. But in a matter of months, the entire foundation of his effort was quaking. When an NRCS computer spit out the location of a Southampton County farm for a random spot-check, the bureaucratic crosshairs zeroed on the name of Charles Hood.

Next in the series: NRCS wants their EQIP funds returned

Chris Bennett works as the Technology and Issues Editor with Farm Journal.