‘Friends’ indeed!

Published 11:59 am Tuesday, June 12, 2018

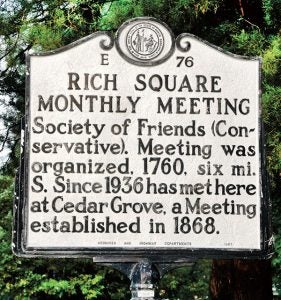

- Established in 1868, the Cedar Grove Meeting remains active today on Main Street in Woodland. | Staff Photo by Cal Bryant

Submitted by P. Michelle Felton

Scattered through the corn, tobacco and soybean fields, at the crossroads of Highway 258, lie hidden the footprints of the Underground Railroad in Northampton County.

The group more historically associated with the Underground Railroad were the Society of Friends, also referred to as “Friends” or the “Quakers”. For purposes of this article they will be referred to as just “Friends”.

As students we recall reading in history books and being taught in middle and high school about the bravery demonstrated by individuals who worked on the Underground Railroad such as Levi Coffin. He was known

as the “President of the Underground Railroad”. Coffin was born in what is now Guilford County, NC and later moved with his family to the free state of Indiana.

Then, there is Harriet Tubman, born into slavery on the eastern shore of Maryland and called the “Moses” of her people. We have heard of Tubman’s heroics, her daring escape from slavery to freedom and then again returning to free others even though there was a price placed on her head in exchange for her capture.

However, there is little recalled about the courage of our neighbors the “Friends” in Northampton County, their

This state historical marker, located on the grounds of Cedar Grove, tells of the 1760 organization of the Quakers in nearby Rich Square.

contributions to the Underground Railroad and valiant peaceful fight for human rights.

Edgecombe, Hertford, Northampton, Pasquotank and Perquimans counties had a modest population of Friends living within the northeastern North Carolina corridor. As early as 1665, the first Friends made their presence in Perquimans and Pasquotank. George Fox, known as the founder of the Religious Society of Friends, and William Edmundson, also an Englishman, traveled from England to the outskirts of Hertford in 1672. At this time, Friends were holding ”meetings” in private homes with conservative forms of their silent services until a formal and centralized ”meeting house” was designated or constructed.

The first North Carolina Yearly Meeting was established near Hertford in 1698. The “Yearly”, “Quarterly” and “Monthly Meetings” were held to conduct business, provide governance to the organization and to provide guidance to its members. These types of meetings were similar to the Protestants’ monthly conference meetings, association meetings and state conventions.

Northampton County was home to at least three meeting houses; the Rich Square Monthly Meeting House, the Jack Swamp Meeting House near Garysburg, and the Cedar Grove Meeting House in Woodland. Members extended beyond Northampton County into Hertford County, especially into the town of Murfreesboro.

The Rich Square Monthly Meeting was established in 1760 after being granted a request from the Quarterly Meeting in Perquimans County. Joshua Daughtry deeded one acre of land for the original meeting house. It was situated near what is now the intersection of Highways 258 and 561 in the center of Rich Square. The meeting house property became increasingly undesirable when travelers littered the area while stopping overnight to sleep on the grounds and rest their horses. Consequently, Friends made a decision to move their meeting house from the center of town to a location just east of Rich Square on what is now Highway 561 and close by the old depot. They purchased the land from James T. Lambertson in 1866 and moved their

meeting house to this location in 1869.

The Cedar Grove Meeting was established in 1868 upon the request of Friends who wanted a meeting house closer to home. Travel by horse and buggy was arduous on the makeshift roadways and when factoring in adverse weather conditions. Cornelius and Elijah Outland deeded the land on which the Cedar Grove Meeting House sits. It was situated next to a Friends school house that educated both genders.

As early as 1768, North Carolina Quakers condemned the importation of Africans, the purchase of Africans and asked members to provide moral guidance to the enslaved individuals they may have owned. Friends were far more advanced than their contemporaries of the day.

Thomas Newby, of Belvidere in Perquimans County, requested advice about freeing or manumitting his slaves in 1774. The Yearly Meeting gave instructions that any Friends wanting to free their slaves should receive permission from their Monthly Meeting. Not all Friends were in favor of manumission.

The same year of the signing of the Declaration of Independence, Newby freed 10 slaves. A year later, Newby and 10 other Friends freed approximately 40 slaves. This drew the ire of the courts and the North Carolina General Assembly. These were precarious times with the colonists fighting against the British during the American Revolution. North Carolina did their part in this fight for liberation. It would have been a honorable and just cause. However, the colonists fought for their rights, at the same time they overtly denied the rights and freedoms of others.

In 1777, the NC General Assembly took efforts to thwart the actions of the Friends toward manumission by adopting an “Act to Prevent Domestic Insurrections”. A portion of that law stated, “

sections of the Act stated: “No Negro or Mulatto Slave shall hereafter be set free, except for meritorious Services to be adjudged of and allowed by the County Court, and Licence first had and obtained thereupon. And when any Slave is or shall be set free by his or her Master or Owner otherwise than is herein before directed, it shall and may be lawful for any Free holder in this State, to apprehend and take up such Slave, and deliver him or her to the Sheriff of the County, who on receiving such Slave, shall give such Free holder a Receipt for the same; and the Sheriff shall commit all such Slaves to the Gaol of the County, there to remain until the next Court to be held for such County; and the Court of the County shall order all such confined slaves to be sold during the Term to the highest Bidder.”

The United States Congress went so far as to validate and reinforce the North Carolina law with the passing of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793.

To avoid conflict with the laws and their philosophy of life, many Friends living in Northampton County made the decision to move north and westward to free states or free-soiled territories. Thus the migration to Indiana and Ohio begin. In some cases, Friends deeded the enslaved they owned over to the Friends Meeting and in other cases the enslaved accompanied them to the free territories where they were freed.

Some of the Friends decided to stay behind and peacefully challenge the disconnect between the charters of freedom (the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution and the Bill of Rights) within an increasing hostile environment from neighbors.

One such Friend was Josiah Parker. Josiah was an elder of the Rich Square Monthly Meeting and lived with his family near Lasker in Northampton County. According to Quaker Records, Josiah made his livelihood as a farmer and miller. He served on a committee assigned the task of providing oversight and protection of the enslaved that had been deeded to the Yearly Meeting. The committee cared for the enslaved until they could receive safe passage to a free territory, state or be legally manumitted.

Glimpses into the life of Josiah and his wife, Martha (Peele) were documented in letters of family members, Friends and family acquaintances that had migrated from the Roanoke-Chowan area to the states of Indiana, Ohio and parts north. The Parkers had three sons to migrate; Samuel, William and Nathan. Correspondence can be found between Josiah and his brother, Jeremiah Parker. The letters shed light on the way of life for Friends. More significantly, the letters share differing views between Friends on the issues of race, religion and slavery.

The centuries old letters were maintained along with business papers and account records belonging to Josiah. The valuable records are a part of the Josiah Parker Collection held at Earlham College in Richmond, Indiana.

The entire collection is both insightful and intriguing. It includes a letter from Hannah Elliott, a former enslaved African-American who was moved from Northampton County to Indiana. Hannah wrote a letter dated September 21, 1829, from Jackson Township, Wayne County, Indiana, to Martha Parker. The letter reflected the close bond between Hannah and the Parker family. Hannah concluded the letter by inquiring about her mother’s husband and his impending trip to Liberia. It revealed Friends’ efforts with the American Colonization Society to migrate a number of former slaves from the Roanoke-Chowan area to Liberia and freedom.

Finally, there was the strength and courage of Henry Copeland, Sr. and Dorothy Copeland. The couple resided about a quarter of a mile east of Rich Square on what is now Highway 561. The Copelands’ residence was a part of the network of homes and places within the Underground Railroad. The house contained a “secret hiding place” where the Copelands harbored the enslaved who were on the move seeking freedom.

The home is no longer standing. Nevertheless, the gravesites of the Copelands are recognized by the National Parks Service (NPS) for the couple’s contributions to the Underground Railroad

Although the meeting houses in Rich Square and Jack Swamp no longer exist, the Cedar Grove Meeting

House remains today. It is here where the past meets the future. Like the Friends that have passed on, its members carry with them a tradition of exploring ways to build a ”more perfect union.” Where there are injustices, they find ways to carefully ensure justice; where there is violence they create peace; and where there is hate they create love. This place, Cedar Grove Meeting House, the house that sits inconspicuously on Main Street in Woodland, a plain white wooden structure with black shutters, shines as a beacon of light and leads us to the footprints of a rich history within the Roanoke-Chowan area.

A special thanks to Barbara Gosney for contributing and making available many Quaker documents for this article; the Cedar Grove Meeting House; the web site at Earlham College containing the Josiah Parker Collection and making this collection available to the public; and Friends Historical Collection at Guilford College.

Schools interested in making field trips to the Cedar Grove Meeting House to learn more about the Friends of Northampton County and the Underground Railroad need to write to Rich Square Monthly Meeting, PO Box 482, Woodland, NC 27897.