Flood earns state’s highest civilian honor

Published 4:04 pm Friday, December 24, 2021

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By Greg Childress

NC Policy Watch

At age 90, Dr. Dudley Flood, an education trailblazer who helped North Carolina’s public schools to integrate, can easily recall attending an all-Black high school.

It was more than 75 years ago in tiny Winton, a town of fewer than 800 residents in Hertford County.

“There was one microscope in my lab,” Flood said. “When I got to North Carolina Central University and we had a microscope a piece, I didn’t know how to tune it. I hadn’t gotten dumber. I just had not been exposed to that.”

Flood graduated from NC Central in 1954, the year the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that racial segregation of children in public schools was unconstitutional.

He would go on to become a teacher and principal and later joined the NC Department of Public Instruction, where he worked for 21 years. He was one of a handful of Black professionals at the department that oversees the state’s public schools.

Ending segregation:

necessary, but no panacea

In Winton, he remembers tough but caring teachers and administrators who ensured students received the best education possible under less than ideal circumstances as they did their best to mask lab equipment deficiencies (and many others) at C.S. Brown High School.

Despite the teachers’ best efforts, Black students in segregated schools received an education that was inferior to the one received by their white counterparts across town in better-funded schools, Flood said.

He doesn’t flinch when asked whether Black students were better off in all-Black schools as some critics of integration insist.

“No, we didn’t have better education,” Flood said emphatically. “We had better treatment, and more caring. We had teachers who took us beyond what the curriculum was. I was one of those teachers, so I know.”

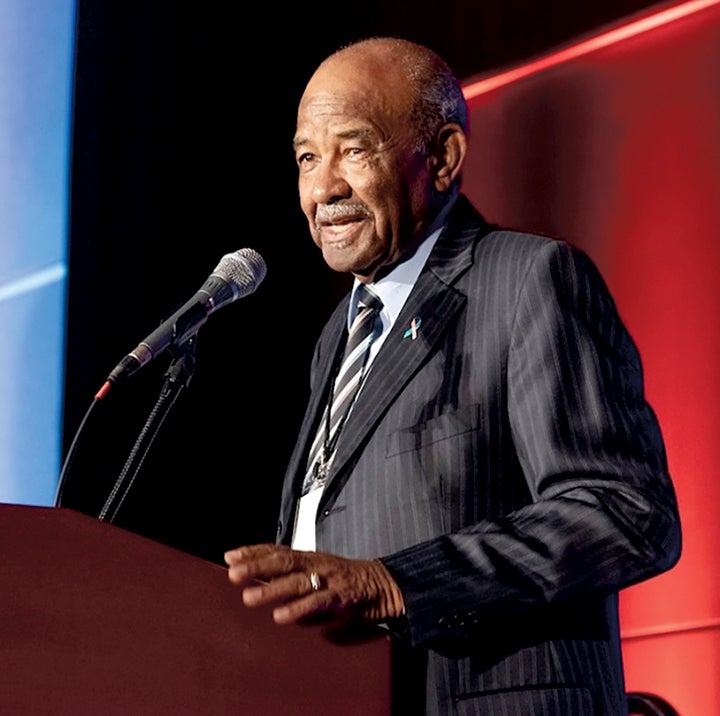

Flood’s comments came last month on the day he received the prestigious North Carolina Award for his historic work to integrate the state’s public schools.

The award is the state’s highest civilian honor. The General Assembly created it in 1961 to recognize significant contributions to the state and nation in the fields of fine arts, literature, public service, and science. Flood was this year’s “Public Service” honoree [

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Flood and his Department of Public Instruction colleague, the late Gene Causby, traveled the state to unite communities divided, sometimes bitterly, over integrating public schools.

It was a tough assignment that met with resistance from whites unwilling to change, and sometimes Black parents distrustful of plans to close Black schools and bus their children to all-white schools.

“There was no other way to integrate our society except through schools,” Flood explained. “There is no other institution through which you could do that because all the other institutions are voluntary. But if you’re in North Carolina, you have to go to school.”

The federal government also held a stick; the 1964 Civil Rights Act gave it the power to withhold federal funding to school districts that refused to desegregate.

Hyde County was a particularly difficult assignment for Flood. There was a school boycott for a full year, and Flood and Causby were sent to the rural county in the northeast part of the state to get students back in schools.

A community meeting was held that resulted in integrated schools reopening the following school year.

Flood spoke at the county’s next high school graduation. The title of his remarks was “Different Does Not Mean Deficient,” a theme he continues to use in his work.

“They went back to school,” Flood said. “Success has many fathers; failure is an orphan. I don’t even want credit for that. I was just one of many players, but they went back to school and the students resumed learning.”

Decades after Causby and Flood worked to integrate North Carolina’s schools, they remain largely segregated by race and ethnicity – a trend that has grown more pronounced in recent decades as federal courts have retreated from past orders that directed local districts to balance schools racially.

The Economic Policy Institute published a report [5] last year that found Black children nationally are five times as likely as white children to attend schools that are highly segregated by race and ethnicity.

Despite these developments, Blacks from older generations often have positive memories of caring teachers, opportunities to lead, and a sense of community they frequently enjoyed at the all-Black schools they attended.

And even today, younger generations of Blacks contend they are better off for having attended predominately Black schools, citing many of the reasons as the generations that came before them.

“My culture was always celebrated and cultivated, not just tolerated,” Toyia Williams said in an online discussion hosted by the Facebook group Black Parents Connect Durham. “I didn’t have to assimilate to try and fit in, I didn’t have to deal with insidious effects of racist microaggressions. The list goes on and on.”

The goals of integration were laudable, Williams told Policy Watch.

“They [Black parents] wanted better facilities and resources for our children,” she said. “However, I’m not sure that I’d agree that the opportunity cost was worth the lasting impact and trauma endured by many students.”

Adequate funding

remains the key

Flood has kept a close eye on the Leandro school funding lawsuit that began more than 25 years ago, noting that there has been little support among lawmakers to address the disparities the lawsuit uncovered.

He said progressives in the Democratic and Republican parties have begun to see the value of improving academic outcomes for all children.

“Now that has changed because they’ve come to realize that if you raise the level [of academic achievement] all ships will float higher,” Flood said. “They’re a little bit more serious about it.”

The lawsuit was brought by five school districts in low-wealth counties that argued their districts did not have enough money to provide children with a quality education.

In 1997, the state Supreme Court issued a ruling, later reconfirmed in 2004, in which it held that every child has a right to a “sound basic education” that includes competent and well-trained teachers and principals and equitable access to resources.

Superior Judge David Lee, who currently oversees the lawsuit, recently ordered lawmakers to transfer $1.7 billion from state reserves [6] to fund recommendations in a consultant’s study to begin to meet the state’s constitutional mandate to provide students an opportunity for a sound basic education.

Flood cautions that money is only one of many factors needed to improve academic outcomes in the state’s public schools.

“You need human support as well,” he said.

He said quality teachers for the state’s 1.5 million schoolchildren are essential to their success.

“If you asked me right now to open a school and you let me pick people who really care about children, who have a good amount of capability, and ask me if I want these people or if I want more money, I’d take the people,” Flood said.

Adequate funding is important, he added.

“It can help you to attract quality people to work for you because they don’t have to work second and third jobs,” Flood said.

Creating “possibility”

These days Flood stays busy with his work at the Dudley Flood Center for Educational Equity and Opportunity he co-founded to address issues of systemic racism and to advocate for structural changes in policy and practice to build an equitable education system. The center is part of the Public Schools Forum of North Carolina (PSFNC).

“It took the courage and dedication of Dr. Flood and his colleague, Gene Causby, to do the grassroots work of uniting divided communities in order to integrate our public schools,” Wolf said.

As he looks back over his career in education and his work to integrate the state’s public schools, Flood has few regrets.

“The whole thrust of dismantling a dual school system was to create possibility,” he said. “The disappointment people have [in integration] is they thought it was supposed to be a cure. It wasn’t designed to be a cure; it was designed to be a possibility. It was the opening of a door. Now whether you walked through quickly, dragged your feet, or chose not to walk through at all, I don’t take much responsibility for that. The opening of the door was my role and Gene’s [Causby] role, and we did that, and I have no question in my mind about that.”